Tatuaje: What is not said is as important as what is.

How people expressed grief at a time when it was illegal to do so

Hi, all. Thank you for subscribing to my newsletter.

The song this week is a song from Spain, 1941. You can read about the background of the Spanish Civil War here. It contains some important information and vocabulary that will help you understand this content.

Note for Japanese students, vocabulary words in bold are provided in Japanese below. A video with the Japanese subtitles is at the bottom of this post.

(664 words)

After the Spanish Civil War, many of the people who supported the Republic or who were opposed to Franco’s takeover of the country were sent to prison camps or exiled. Thousands were shot after the war ended. Franco and the military were in control. The Falangists (the only political party allowed in Spain at the time), and the Civil Guard maintained “law and order” in the streets. Union activity was punished. Women’s freedoms were severely restricted. El Caudillo (the Leader), Franco, declared that there would be no mourning - on either side - of those who had been lost during the war. Many people were not allowed to bury their dead.

This set up a terrible dilemma for the survivors of the war. Thousands of people on both sides had seen family members arrested, murdered, or tortured, and now they were being told to keep silent about everything, to put on a smile and act as if it had not happened at all.

What happens, psychologically, when grief cannot be expressed? Today, we understand that grief, like other kinds of emotional pain, must be expressed. Not doing so could lead to physical illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, or high blood pressure. Talking about what happened - expressing it - is a first step toward healing, yet that was blocked.

The losers of the war were treated as less than human, worthless, and were blamed for everything that had happened during the war. On top of this, they suffered from the chronic terror of being found out and turned over to the authorities. There was remaining traumatic stress from the war, and everyone in Spain was enduring the lack of food.

How did people deal with this situation during “the time of silence”? How did supporters of the Republic manage to find meaning in living?

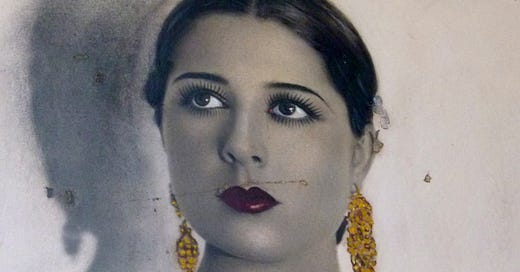

Conchita Piquer sang coplas. The copla, a ballad, is a style of music based on flamenco and one that was often acted out in theaters. Conchita Piquer’s songs were also heard on the radio.

Conchita Piquer sang coplas about people in society who were disadvantaged and powerless. One such song, from 1941, was called Tatuaje, (tattoo). The song is about a woman, the person singing the song, who meets a sailor who is tall and blond. Over glasses of brandy at a bar, he tells her about his past. He loved a woman, but she turned him away. He can never forget her. He shows the singer the tattoo of the woman’s name. The singer falls in love with him, but the sailor soon leaves port. She goes from bar to bar, and over a single glass of brandy, asks the sailors who come in if they have seen him. She shows them the tattoo of his name on her arm.

The song had a double meaning for the people of Spain after the war. The tall, blond sailor could have represented a family member, a lover, a child (children of Republicans were often taken away, later to be raised by right-wing families), a friend, or a foreign fighter who came to help fight in the war. So many people had disappeared and were still disappearing, and their families could get no information about them. This was also true for the right-wing families who had sons or boyfriends who were fighting abroad.

By singing this song, people were able to express their grief by performing the role of the singer in the song. In this way, expressing one’s sorrow was acceptable in society. It was also a powerful way to oppose Franco’s control. By singing this song, people promised to continue their search for their missing loved ones. By singing this song, the survivors promised to always carry the name of their loved one - like a tattoo - burned in their memory.

This song and others like it allowed the survivors of the Spanish Civil War to deal with their grief in both an open and clandestine way.

Never underestimate the power of songs.

VOCABULARY

takeover 買収

exile 追放

severely 散々

restrict 自由がきかない

declare 宣言済み

mourning 追悼

bury 葬る

survivors 生存者

psychologically 心理的に

grief 嘆き

blame 責める

chronic 恒常的

being found out ばらる

endure 耐える

disadvantaged 社会的弱者

right-wing 右翼的

sorrow 哀しみ

clandestine 隠密

underestimate お見逸れ

Source

Survival Songs: Conchita Piquer’s Coplas and Franco’s Regime of Terror by Stephanie Sieburth. 2014. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

The song with English subtitles (but a different visual story):

Fascinating, Louisa.

Wow, this song would have been beautiful enough without the story behind it, but the history elevates it to a new level. I think people's forbidden emotions come out no matter what, but it is always interesting when they come out on purpose. The use of music as a secret message reminds me of slaves using "Follow the Drinking Gourd."

Do you know where the video accompanying the English-subtitled version of the song came from?