Hi all,

Thank you to all of my subscribers and a warm welcome to new visitors!

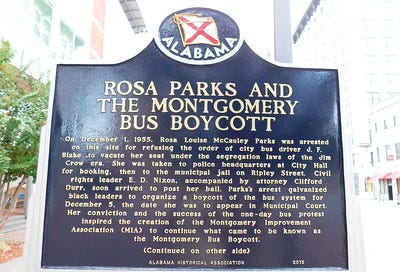

This week’s song is Alabama Bus, by Brother Will Hairston, a song sung by people during the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1956. Even if you know about the boycott, you might find the background information on my website quite interesting! Did you know that there was a very important group of women who were responsible for the success of the boycott? You can read about it here.

If you’d like to hear the song before you read the background, I’ve included a YouTube video below with lyrics in English.

Below, you’ll find my interpretation of the lyrics. I’ve written the lyrics in italics. As with most everything, there are many ways to interpret things. If you have any questions or comments, please feel free to leave them in the comments section at the bottom.

For Japanese students, vocabulary words in bold are provided in Japanese below. There is also a “Pronunciation Extra” at end below the video.

The Song

(460 words)

Alabama Bus was written in 1956 by Brother Will Hairston in Detroit, Michigan, in the U.S.

The song is sung in the form of a story told by a person who was part of the thousands of people who decided they wanted to end segregation on buses in Montgomery, Alabama.

Before the bus boycott, both black and white passengers rode the buses, but the blacks had to take only the seats in the back of the bus. If a white passenger got on the bus and there were no seats available, a black person had to stand up and give the white person the seat. Looka here, man, you’re from the Negro race / And don’t you know you’re sitting in the wrong place?

The man told the driver: “My feets are hurtin” (my feet hurt) /The driver told the man to move behind the curtain Here, curtain refers to the line dividing the white section from the black section of the bus. The position of the “curtain” changed depending on who was riding the bus.

The lyrics go on to talk about Reverend Martin Luther King, who was a strong man, similar to Moses in Israel. Moses was a prophet and leader of the Israelites when they were slaves in Egypt. He led them out of slavery.

A man ain’t nothin’ but a man could refer to the fact that under slavery in the U.S., black men were called boy, even as adults. Being called a man implies that you are a full human being.

The lyrics explain how, like Moses, Dr. King led his people to defeat the segregation laws in the U.S. One way was to support the bus boycott: All of my people gonna walk to work.

The bus company tried to frighten the boycotters by threatening them with arrest: Cause don’t you know you broke the anti-boycott law? Many were arrested, and the bus company knew that they did not have the money to pay for their bail to be released.

They had the trial and Clayton Powell was there. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. was another leader in the Civil Rights movement. He had led a bus boycott in New York much earlier than the one that happened in Montgomery, but it did not receive much media attention. He later became a Congressman from New York.

Diggs went down there to go his bail. Charles C. Diggs, Jr., was a Congressman from Michigan. He collected donations (You know, they sent a lot of money, saying, “King go on”) and was able to pay the $500 bail for boycotters who were arrested.

Rev. King was born on 15 January, 1929. He went on to become one of the most famous leaders of non-violent protest in American history.

————

VOCABULARY

segregation 人種隔離

passenger 乗客

prophet 預言者

slave 奴隷

imply 意味

frighten 脅しつける

threaten 脅す

bail 保釈金

—————

Notes

You can learn more about Brother Will Hairston at:

https://marshamusic.wordpress.com/the-alabama-bus/marshamusic.wordpress.com Marsha Music is a great site to learn about music of the 1960s!

Pronunciation extra!

The way we write and the way we speak is often quite different. For example, “Do you want to…” is often pronounced [dʒə'wa:na:] which could be written as djawanna. (We don’t usually write it this way, however.)

In this song, there are a couple of examples of this, especially in American pronunciation:

wanna = want to

gonna = going to

Another example is the way we pronounce words ending in “ing”. We often pronounce a word such as wishing as ['wɪʃn] and sometimes write it as wishin’, dropping the final “g”. In academic or business writing, we would spell out the word(s), but in novels and songs, you might find the shortened versions.

The courage of these people amazes me every time I hear this story. My policy is often to not go where I'm not wanted and yet these people knew there was no reason they shouldn't be wanted and so they went. And now they are wanted. There is a lesson to be learned even today that we need to spend time with those who hate us. It will stop some of the ideological division in the world if only they can see that the other side is full of human people who we must deal with on a regular basis.